They’re easy to spot come May, strutting about campus with a sense of belonging, beaming with pride in this bucolic place. How could they have not spent more time here, they wonder? They are greying in spots, heavier than they were in their college days but, now, put together, polished by the years, and confident.

Look closely, however, and you’ll see subtle tells that belie their confidence: eyes adrift in the middle distance, pained expressions—loss, yearning, melancholy, loneliness—darting across their otherwise happy faces. Caught in their thoughts, some of the more wistful ones seem almost stricken, gripped by a momentary vertigo, one that is as irrational as it is raw. It's as if they’ve suddenly sustained a mortal blow walking through this leafy quad. They haven’t. They have simply raised children. They have watched them bloom, and, on this day in May, are bearing witness as their now not-children, like dandelion seeds with evolution-perfected fluid dynamics—take willy-nilly to the air. Dumbfounded and earthbound, these parents are left to wonder: Did we get the physics right?

It's easy to dismiss, I suppose—a problem of the privileged. Still, it’s heartache like any other heartache, at times both crippling and fraught with revelation.

This year, I am in the curious situation of having a daughter graduate from pre-school while another daughter graduates from college. Our modern family just worked out that way. And as every two-bit psychologist, parenting blogger, or actual sleep-deprived parent will tell you: Transitions are a bitch. They trip up parents as much as they do the kids, maybe more so.

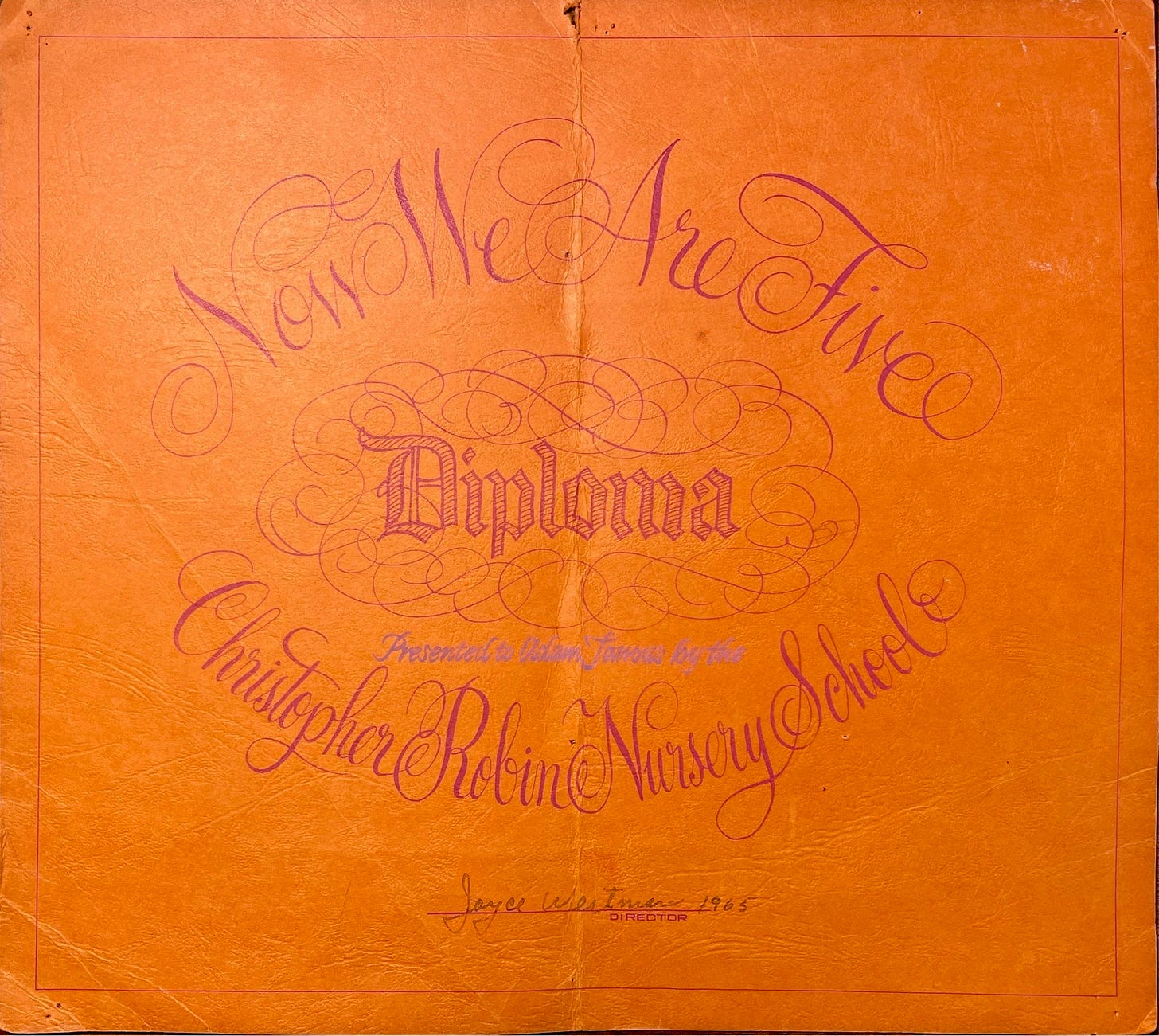

I don’t remember much from my pre-school graduation, except for the fact that I did get a diploma: bold orange, heavy stock paper that reads: “Now We Are Five—Christopher Robin Nursery School.” The Christopher Robin Nursery School was a happy little place that abutted another happy little place—the Dutch Goose—a beer and burger spot that catered to the nearby college students.

When it came to my college graduation, we had our ceremony in a football stadium that was a bike ride away from the Dutch Goose. The then Secretary of State, George Shultz, told us soberly:

“In an age of nuclear weapons, maintaining collective security is no easy task. We must both defend freedom and preserve peace. We must seek to advance those moral values to which this nation and its allies are deeply committed. And we must do so in a nuclear age in which a global war would thoroughly destroy those values.”

All these years later, the idea of moral resolve in the face of mortal danger is just as relevant and just as a noble a pursuit. However, I can’t say that I’ve ever been at that particular intersection, but I do respect Mr. Shultz’s sentiment. What he didn’t need to say at the time but now seems crucial to his argument is this: Tactics matter. Sometimes the morality of the tactics tarnishes the moral value of the cause.

Our college president at the time, the late Donald Kennedy, spoke after Mr. Shultz. Avuncular, approachable, and wise, Professor Kennedy—quoting Adlai Stevenson—said something that has stuck with me for decades:

“Your days are short here; this is the last of your springs. And now in the serenity and quiet of this lovely place, touch the depths of truth, feel the hem of Heaven. You will go away with old, good friends. And don't forget when you leave why you came.”—Adlai Stevenson

“And don't forget when you leave why you came.” As a 22-year-old, I took him quite literally: Why did we go to college? Because it is what relatively privileged kids do? Because the statistics say you are likely to avoid prison? Because your projected income will be higher or that you want to make your parents proud? Because you would never make it in the military?

In retrospect, it seems college is an exercise in humility, which is a good lesson for sure. For the first time in your life, context has no place. That you had a 3.94 GPA, counting your AP classes; or that you won every soccer game you ever played; or that you speak Mandarin; or that you can play violin while speaking Mandarin—none of it has relevance in this newly levelled world. Everyone is impressive. It is just you, a wealth of ideas, and people who don’t know you. In this new reality, what you say and do reflects on you, not your parents or anyone else. You are now a person that must answer to the world.

“So, pack up your car, put a hand on your heart. Say whatever you feel, be wherever you are.” —Noah Kahan

I am aware that every generation of parents feels that their graduates are facing a more difficult world than any others. That being said, I still believe that this class of parents—of which I am a member—is watching their dandelions drift off into a much more turbulent atmosphere than certainly my parents did.

There is an undeniable dystopian feel to things—not so much an end-of-the-world feeling per se, but the anger and intolerance, the sectarian and partisan divisions that are hardening—if not fully hardened—are breathtaking. There seems to be no possibility of being wrong in this brave new world. Ironically, it is an attitude antithetical to the very essence of college, where everything is considered, where argument is a prerequisite for learning rather than the point from which to draw a battle line.

I’d venture to say that most parents of this generation feel a little helpless and, if not guilty, partly responsible for where things have landed. I doubt that any of us are pleased with the culture of retribution we find ourselves in.

What’s more, never before have young people been bombarded with so much nonsense—A.I. deep fakes and hallucinations, “alternative facts,” and “influencers” and Tik Tok “creators” whose guiding principle seems to be what Mark Knopfler sarcastically immortalized in song: “Get your money for nothin’.” Sadly, the ether is filled with such misdirection.

During COVID, a friend walked into a rural country store in Central Idaho wearing a mask. The clerk, a leathery, hard-scrabble woman of 90 angrily barked at him: “Why you wearin’ that mask? Don’t you know that COVID can go right through porcelain?”

“No ma’am, I did not.”

So, what to do in the face of madness?

Like everybody who has lived a decent chunk of time, I have been showered with all kinds of advice and wisdom from those above me in age or position. It has come from people with gobs of money and some without, from Nobel Laureates and great writers, from my parents who had remarkable and enviable lives, and from my dearest grandmother, Sara Tanous, who lived through the invention of the airplane, the advent of automobiles, the Depression, two World Wars, the Civil Rights Movement, the nuclear age and Cold War, the landing on the moon, and the computer revolution.

Then there was a letter I once found, one my mom had written to a friend just before dying of cancer. She wrote:

“The point is not that one should learn to live a little, but rather that one should live to learn a little … a little compassion, a little understanding, and, eventually, a little humility.”

Even though the words weren’t meant for me, I hold them close as if they were.

All of the wisdom from above notwithstanding, I sometimes wonder if instead the truest wisdom has been bubbling up from below.

I spend a pretty good amount of time with 5-year-olds, in particular my younger daughter and her pack of alpha wolf girlfriends. What have I learned from them? Simply, that joy is the currency of life. All you’ve got to do is find it, which is not that hard. Five-year-olds can find it in little penny treasures hidden in a tanbark playground.

What is remarkable about joy is that it defies all the laws of conservation we study so diligently in college: mass, energy, momentum, electric charge. Joy is contagious, unlimited, self-perpetuating—an abomination of our understanding of the physical world—but so it goes. Think of it as a 5-year-old might: a magical river to swim in, one unbound by gravity, and one that just might take you wherever you are going.

“… don’t forget when you leave why you came.”

And so, at last, I come to this: Our greatest joys are those who will leave us. They are the closest we will ever come to having a mortal wound we must survive. They, Mr. Stevenson, are why we came to this lovely earth.

Adam, You brought so many fleeting memories back to me this morning, back to my early years and then leaving the Stanford days behind....and you brought so much context to it all, plus having me in tears.Thanks you for your gift....that you give to so many. Sending your words on to my grandson graduating from college this week and another finishing up at the community school.

Fondly, Betsy Gates

🥹 Beautifully written Adam! So much of this resonates for me. Thank you for this poignant reflection ❤️