I’ve always loved going to the dump. When I was a kid, the dump was out by the San Francisco Bay, and there was a certain beauty to the place, at least in my memory, which admittedly has become more forgiving in time.

The air had a briny but surprisingly fresh smell to it. Seagulls were always in the air, great white flocks of them wailing above enormous mounds of trash that stretched as far as I could see. Men in bulldozers were climbing the mountains, pushing the leftovers of life this way and that. As a little boy, I was captivated by them. While I couldn’t discern their methodology, I knew there was one to be discovered, and that kept me transfixed by the scene. It was thrilling to a 7-year-old to watch vehicles—in this case giant Caterpillar front loaders—indiscriminately drive places it seemed they didn’t belong: up, over, and sometimes through refrigerators, cribs, couches. Up and down they went, ceaselessly shaping all the things no one wanted. At the dump, there seemed to be no rules. It was regular life turned upside down, and there was something invigorating about that.

Going to the dump was also an experience inextricably tied to my dad. He and I would go together, along with a string of dogs over the years: Duke, Charlee, Prix, Ben. They were all hunting dogs, so my dad always used the occasion to stop at the marshlands nearby. He and I worked the dogs there. I would throw a rubber bumper as far as my skinny little arms could muster into the wetlands, my dad holding our dog, in this instance, Charlee, by his side. Seconds that seemed like minutes went by. Then, when the dog’s quivering anticipation was about to burst, my dad would release her with the simple command: “Charlee!” Charlee would explode from her sitting position, sprinting toward the water as if her life depended on it. At the water’s edge, she leaped, her 60-pound black Lab frame fully extended. For a moment, she was suspended in flight—pure black magic in the air. Crashing into the water, she swam head up, silently but furiously to the bumper, grabbed it in her mouth and swam to shore. Back at my dad’s side, she waited for the command: “Drop.” And then Charlee’s celebration began.

It was the simplest of joys to watch but thrilling every time.

Going to the dump is a tradition I have carried on with all three of my kids over a span of 20 years or so. Dumps today, at least where I live, look nothing like the ones I grew up with. Everything is segregated, relatively clean, organized, controlled, and, of course, less fun. And it’s not called a dump, rather a “waste transfer station,” an anemic name for a dump if you ask me. Nonetheless, my kids did and still do love going out there. Maybe it’s all the earth moving equipment— “diggers,” as they say. Or maybe it’s the drive on slow county roads to get there, the open air, the scale of the place, the thrill of tossing things out of a truck; I don’t know, really.

While I’ve never owned a pick-up, my neighbor for many years did. I think going to the dump was how we became good friends. He is a few years older than I and grew up in a very different world than I, but somehow those trips to the dump brought us together. We talked and laughed and yanked piles of brush out of his truck. We added them to the towering walls of brush and tree limbs out there. We would talk some more, then maybe do an errand in town together that we didn’t really need to do. My neighbor has since moved, and trips to the dump alone just aren’t the same.

I’m generally not one to split the world in two, as in “there are lovers and haters,” or “the world has glass half-full people and glass half-empty folks.” I think most people are more conflicted about most things. That being said, I do think there tend to be this-clutter-is-in-my-way-throw-it-out types and the save-everything-for-this-or-that-contingency types. I suppose I fall into the thrower group, the less defensible of the two. When confronted with old T-shirts that could be used for painting, replaced coffeemakers, pens that sort-of work, I toss every time and without much guilt.

I know this is not an admirable quality. We should not be a throw-away society. I’m hoping mine is a generational flaw. Or perhaps an educational one. My 4-year-old daughter sees things differently. When she gets a new T-shirt, the first thing I do is cut off the tags and head to the garbage with them. To this I am met with a nearly desperate wail, “No, dad. You can’t throw that out! We can glue that to something, can’t we?”

I don’t know where she learned her glueing philosophy—not me, I know that much—but I applaud it. Take trash destined for oblivion, glue it to something and make something better.

Clearly, the throwers—to the world’s detriment—have had their way with the world up until now. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, which tracks all types of our waste and where it goes, Americans generated 584.8 billion pounds of what we used to call garbage in 2018 (latest available figures). Now the term is municipal solid waste (MSW), which I suppose sounds cleaner and less threatening. Regardless, that comes down to 4.9 pounds per person every day of the year.

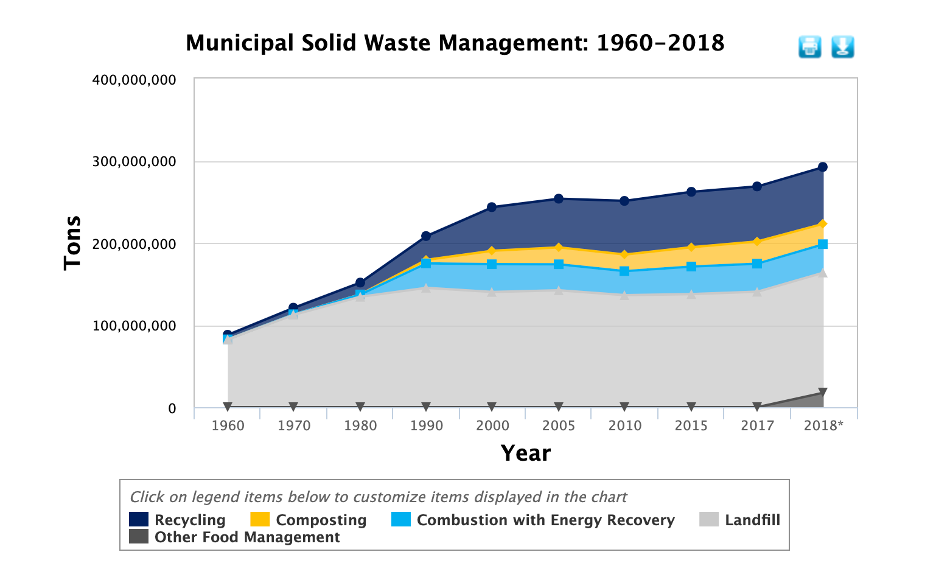

The good news is that we recycle or compost a decent amount— 32.1% —of those 584.8 billion pounds. Combustion of MSW with energy recovery of that combustion amounted to 12% in 2018. Another 6% of the MSW, namely food waste, was managed via animal feed, bio-based materials/biochemical processing, co-digestion/anaerobic digestion, donation, land application and sewer/wastewater treatment.

Still, that left us with about 50% of our generated MSW, or 292 billion pounds, to put in landfills in 2018 alone. The average density of MSW is about 20 pounds/cubic foot. Do the math and you get 14.6 billion cubic feet of garbage, which is the same as 335,000 acres covered a foot deep in garbage. Generate that much garbage for just 10 years and you could walk every inch of the state of Connecticut and always be up to your shins in waste.

Back in 1960, we generated 2.7 pounds per person, or 176.2 billion pounds, considerably less than today, but back then we also put 94% of it in landfills versus 50% today. So, at that rate after 10 years, about 60% of Connecticut would have been covered a foot deep in garbage, leaving 40% of the Nutmeg State available for a picnic or a game of catch.

The EPA data for MSW generation and what we’ve done with it over time is illustrated in the graph below.

For some, graphs can be a bit abstract. If you really want to sense the dilemma of landfills, go to an island. There’s nowhere to hide all the waste on an island. When Hurricane Dorian hit the Bahamas in 2019, one of the dumps on just one of the 30 inhabited islands there burned trash 24 hours per day every day for six months and still the piles grew. Three years later, enormous piles of trash remain to be burned. Maybe they’ll just be left in piles. Or maybe another hurricane will come along and blow it somewhere else. But the rub is, it’s got to go somewhere.

All of this is not to say I am living by some sort of Buddhist monk aesthetic. In fact, I like things, even love some things. I have an old French corkscrew that was my mom’s. There was nothing particularly special about it except the fact that she loved it. She always raved about how well it worked, how old and simple and dependable it was. It was just a corkscrew, but somehow, she had made it hers over the decades.

Years later still, it sits in my drawer. Every time I pick it up, I think of my mom. Invariably, a memory of her spins off from the moment. For an instant, she is there, a full force in my life again. It is a case of an object opening a door to real thoughts and memories. Certainly, those memories are always there, but without some nudge from the material world, they might be irretrievable.

Once, I casually mentioned to my then toddler son that the corkscrew belonged to his grandmother. For years, every time he saw it, he reminded me, “Daddy, that’s Paula’s.” That corkscrew made a connection, however faint, to a woman he never had the chance to meet. It bridged three generations, tied together two lives that were too far apart in time to connect.

Why do certain things in our lives touch us? I think because some possessions simply endure. They survive all our traumas and dislocations. They are there in the corner of the room for all those years, the good and the bad. And because they are always there, they offer some security and semblance of permanence and continuity in an otherwise changeable and transient life.

I tend to think of those special items in our lives like the blankets toddlers carry around. In actuality, we don’t ever really possess anything. We just drag things around with us for a while. Ultimately, they outlive us. The magic of some of them, however, is that, eventually, people rub off on them. Just as a blanket will always hold the essence of a child long after he or she has left the room, our oldest, dearest possessions become imparted with the emotions of our lives.

When we finally leave the world, we leave our possessions behind. They have no place where we are going. The do have a place here, however. They remain for others to find, pick up, rub between their fingers, wonder about all they cannot touch.

And there is another possibility: Just maybe someone will discover them, glue them to something and come up with a trinket even more magical.